Page 103:

Rue François Miron: “Sarah stands in the windows’ sunlight looking out on the two half-timbered medieval buildings that Laura promised in one of her letters. They’re among the oldest in Paris. The roof-lines are pointed, triangular, like a child’s drawing of a house.”

Page 106:

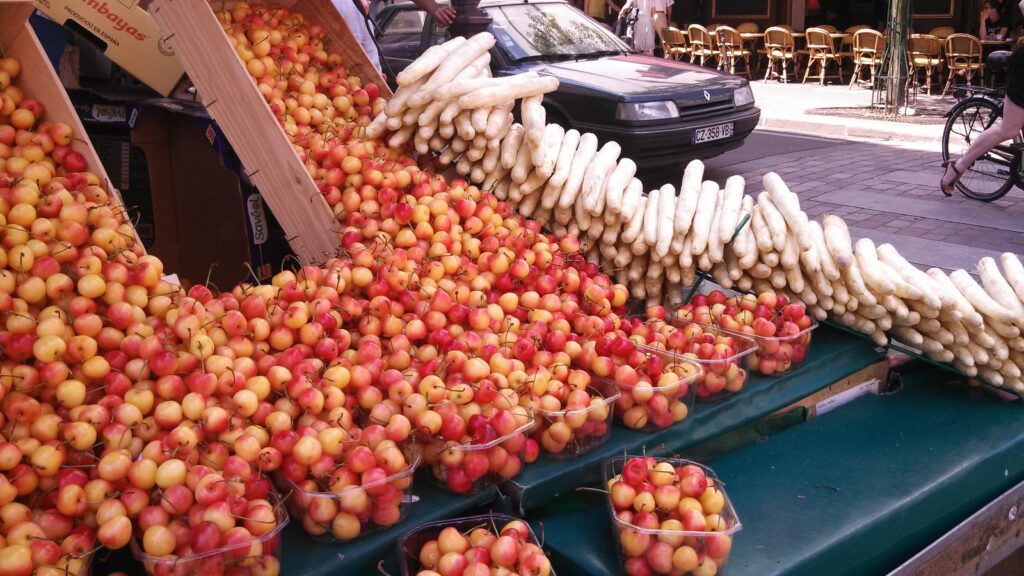

Rue Saint-Antoine: “They pass pâtisseries, hardware stores, fabric stores, their windows crammed with goods. Fruit and vegetable shops with elaborate displays: intricate pyramidal mountains of cherries, carefully heaped, orderly piles of white asparagus-like stacks of logs.”

Page 110:

Place des Vosges: “The heart of the heart of Paris. So much light. The square is big, much bigger than she remembered it. It’s early Saturday morning, so in the strict geometry of the place with its circles and squares, its precision gardening, there’s almost no one. The square is a perfect square, a model of symmetry, the same arcade running along all four sides, paths in perfect diagonals across the inner square. Lines drawn to let people in, not just keep them out. A space that can belong, at least temporarily, to anyone passing through[…]”

(Laila) “In this fountain water spills off the top urn and then the top basin, a little wind catching so it falls crooked there. But at the second basin, the water moves through narrow pipes spouting through the mouths of lions. Paris lions. My father told me that he saw the Lions’ Gate in the walls of the Old City in Jerusalem once. The Lion of Judah, the Lion of Jerusalem. The lions carved into stone there centuries older than these. The ones here are worn so that each lion’s head has been changed to wear a slightly different look. Bored with us, maybe, or maybe curious. Patient. The water keeps spilling itself.”

Page 109:

rue de Birague: “It’s a narrow street that seems as if it were made just for her, ending in a fairy-tale castle façade whose roof is punctured by dormer windows. If there are chambres de bonne way up in those top storeys, there must be precious little light available through the tiny windows for the maids inside.”

Page 128:

Closerie des Lilas: “The restaurant is squeezed in implausibly where the two famous streets meet at a sharp angle. Closerie des Lilas. Lilas means lilac; somehow Sarah knows that. Knows it and suddenly can smell the lilacs outside the window of her bedroom on Rupertsland, their scent almost dizzying. Rose has checked under Sarah’s bed for a wolf, tucked her in, and they’re both breathing the smell of lilacs. She knows the word lilas, from the inside out, but what can closerie mean? She’ll have to look it up, though the paperback French-English dictionary she brought to Paris isn’t much good. After, when she looks it up in the big fat Harrap’s she has at home, it’s still not there, still a small impenetrable mystery.”

Page 155:

Beehives, Luxembourg Gardens: “They come up on a cluster of square wooden hives behind a pale wooden fence, the sun so brilliant that the hives’ tented roofs seem white in its light. A little city of hives. The hives are perched on metal platforms of some sort. Their wooden walls have been polished to a beeswaxy sheen by age and weather. And those pitched roofs on them – like straw rice-paddy hats or pagodas topped by knobs that probably are handles for lifting the roofs off to access the honey.”

Page 142:

Jeu de Paume: “The museum is a long rectangular box with four large dour columns at the entrance. Laura says it used to be a handball court: word for word, jeu de paume means game of palm.

Page 149:

Grand Bassin, Luxembourg Gardens: “Charles is supposed to meet her in front of the Grand Bassin, which is a funny shape, an uneven octagon, two sides longer than the others. Sarah’s taken a seat on one of the little metal chairs sprinkled around the edge of the pond where the immaculate French children are sailing their wee boats on the placid water. Just the lightest breeze today, so the little multi-coloured sails are a bit lax. The stone lip around the pond takes an elegant slow curve to its rippled edge, but that curve seems a bit dicey for the toddlers leaning towards the water with its tempting ducks and wooden boats. The mothers are nonetheless nonchalant, smoking, flipping through magazines.”

Page 160:

Marché d’Aligre: (Laila) “At the Marché d’Aligre market the piles of food set out in the stalls are bright, gleaming. It’s a long walk to the Marché d’Aligre from my room, but the prices are good here. I can buy anything: lettuce, grapes, cheese. Eggplant, lemons, garlic, mint. I could cook a meal, if I had a kitchen. I could make food I remember. I touch the bills in my pocket, the money I worked for, the dull feel of the paper.”

Page 167:

Guimard subway entrances: “Guimard is famous for designing the green entrances to the Métro. He’s back in fashion now, Laura says, but when the Métro station entrances first were built, people hated them. They called his designs le style nouille, noodle architecture, to make fun of all the droopy green flourishes.”

Page 209:

Rue Ferdinand Duval: “She’s a few buildings up the street when she notices, peripherally, a shop window that feels familiar. She turns back a few steps. Bazar Miriam. A little store whose shop windows are crammed with an odd-ball display of kippahs and menorahs and mezuzahs, inexpensive Seder plates, yahrzeit memorial candles. A window full of tchotchkes, her dad would say. There are Star of David and chai necklaces too, though none identical to hers. She touches her neck, startles for a moment because the chain isn’t there. Feels in her pocket for the penny, gives it a few turns. What a jumble of merchandise in that window. If everything were written in English instead of French, the shop would be right at home in North End Winnipeg. She’d be right at home. She must be near the Pletzl. She hadn’t noticed any Jewish shops before. She’s tempted to go in, smell the musty smell of sanctity, community.”

Page 183:

Place Vendôme: “Sarah walks out into Place Vendôme. A couple get out of their chauffeur-driven black Mercedes, head up the red carpet into the hotel. Behind them, a man in uniform is brushing invisible bits of trash into an elaborate monogrammed dustpan. The Ritz. How does he feel about the Ritz, how much is he earning working at the Ritz? She doesn’t even know what minimum wage is here in Paris. And what on earth is she doing at the Ritz, what is she doing in Paris? What does she want from this city?”

Page 209:

Rue des Rosiers: “And suddenly she’s there, at the Pletzl, which isn’t a square at all but a nondescript triangle. She checks the street signs and finds she’s been wandering up rue Ferdinand Duval and now has found herself at the point where it meets up with rue des Rosiers. Here she is in this anonymous space, a place she’s taken herself to without knowing it’s where she’s supposed to be. This arbitrary meeting of irregular streets, the famous Pletzl, is more an intersection than a square.”

Page 210:

“She should go in, get them a table, since it’s pretty crowded, but instead she studies the façade of Rosenberg’s. It has the feel of a child’s drawing: above the arched doorway are crude little schematic flowers picked out in tile, the borders circling them black against the bright, impossibly cheerful yellow of the mosaic tile – no colouring outside the lines! The windows are cluttered with notices and placards: specialists in all kinds of smoked fish, caviar, salmon, sturgeon; blinis with sour cream.”